Seven years have passed since the criminal probe into large-scale corruption in the North–South Road Corridor project began. Centered on the 2009–2018 implementation phase, the investigation—like the highway it scrutinizes—remains stalled, with no end in sight.

Experts are increasingly voicing concern that the case may eventually collapse. They warn that the proceedings already sent to court, having been separated from the main investigation, are at risk of being dropped due to statutes of limitations.

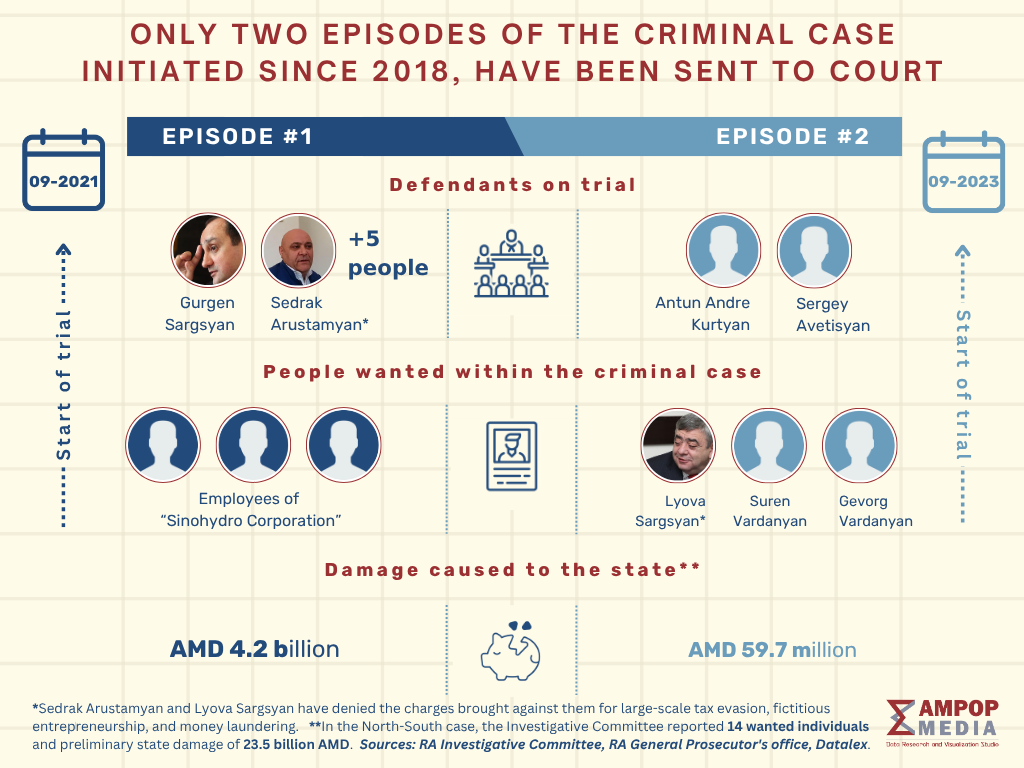

One of the few visible “achievements” of recent years has been the referral of two case episodes to court. However, even those trials have yet to reach a conclusion. To date, no one has been held accountable for the misappropriation of billions of drams.

Ampop Media has sought to understand why the case has remained stalled for seven years, and what risks may arise from its prolonged delay.

An “Unprecedented” Investigation Going Nowhere

In September 2018, Armenia’s Prosecutor General’s Office announced the launch of a criminal investigation into apparent large-scale abuses within one of the country’s biggest infrastructure projects. According to law enforcement, between 2009 and 2018, government officials involved in the North–South project caused 23.5 billion AMD (around USD 60 million) in damages to the state. Notably, this figure was cited as a preliminary estimate. Officials have not clarified what the final amount of damages might be.

The Investigative Committee of Armenia, which is overseeing the case, considers the North–South investigation to be “unprecedented” in scale. Hundreds of individuals have been questioned, dozens—including former high-ranking officials—have been charged, and 14 suspects are currently wanted. Among them is Lyova Sargsyan, brother of Armenia’s third president, Serzh Sargsyan.

The case, initiated in 2018, focuses on irregularities identified in Tranche 1 (Yerevan–Ashtarak and Yerevan–Artashat sections) and Tranche 2 (Ashtarak–Talin section) of the highway, which were commissioned in 2016. The Investigative Committee has not disclosed which specific episodes are being examined.

Already in 2018, the Prosecutor General’s Office had stated that government officials involved in the roadworks between 2009 and 2018 had included inefficient and unjustified tasks in project contracts. According to law enforcement, these officials agreed to extend construction and consultancy deadlines without providing justification or seeking compensation for losses incurred.

The Prosecutor General also reported that in some cases, payments in consultancy contracts exceeded legally allowed maximums—sometimes by double. Moreover, the services provided included redundant and unnecessary work. Authorities also noted that the Yerevan–Ashtarak and Yerevan–Artashat roads were delivered with obvious flaws in the concrete surface, as construction standards for materials—particularly the composition and quality of cement—had been violated.

Only Two Episodes Have Reached Court Over Seven Years

In the seven years since the investigation began, only two episodes from the North–South criminal case have been sent to court. The first involves Gurgen Sargsyan, who served as Armenia’s Minister of Transport and Communication from 2008 to 2010, and Sedrak Arustamyan, the director of “Multi Group” company and a close associate of businessman Gagik Tsarukyan. The second case centers around Lyova Sargsyan, brother of Armenia’s third president, Serzh Sargsyan.

The first case bundles together 13 separate criminal episodes related to bribery, patronage, tax evasion, and money laundering.

Seven individuals are currently standing trial in this case, including Gurgen Sargsyan and Sedrak Arustamyan. They are accused of engaging in fictitious business activity and evading large amounts of taxes. Arustamyan, 58, who is also involved in other criminal cases, faces additional charges of laundering particularly large sums of money.

According to the Prosecutor General’s Office, Sargsyan, Arustamyan, and businessman Suren Avagyan received payments from the Armenian branch of “Sinohydro Corporation,” a contractor in the North–South project, for services that were never rendered—evading nearly 2.7 billion AMD in taxes. Law enforcement authorities claim the abuses were carried out in coordination with the Chinese company.

After the launch of the criminal proceedings, Sedrak Arustamyan transferred 1 billion AMD to the Investigative Committee’s deposit account in 2020 as a guarantee toward possible damage recovery, according to official reports.

Representatives of “Sinohydro Corporation” are also implicated in the case. However, their names are not listed in the materials of the trial currently underway in the Yerevan Court of General Jurisdiction, which legal experts say could indicate that they, too, are on the wanted list.

According to the Investigative Committee, Lyova Sargsyan—who at the time held the position of Ambassador-at-Large—used his influence in the selection process of subcontractors for the North–South project. In 2014, he allegedly demanded, through an intermediary, 50% of the anticipated profits—over USD 140,000 (around 59,710,000 AMD)—from the director of one of the companies selected to install lighting systems along the road. Case files indicate that the money laundering scheme was carried out with the participation of representatives from the subcontractor company “Poli-Transport.”

Suren and Gevorg Vardanyan, owners of “Poli-Transport,” are also wanted by law enforcement.

In this case, only two defendants are currently on trial: businessmen Sergey Avetisyan and Antoun Andre Kourtian.

In effect, over the past seven years, neither the pre-trial investigation nor the judicial process has produced tangible results. Despite the scale of corruption involved in the North–South project, no high-ranking official has been held accountable to date, and several defendants remain abroad and under international search.

Why the Investigation Remains Stalled

While the North–South criminal case remains effectively deadlocked—with no one yet held accountable for large-scale corruption—government officials frequently boast about the amounts of money and property recovered by the state through other anti-corruption cases.

In a statement issued in May, Prosecutor General Anna Vardapetyan announced that approximately USD 247.7 million had been recovered by the state in 2023 and 2024 alone, “including through the application of the asset forfeiture mechanism targeting illicit property.” Between 2018 and 2022, another USD 290 million had been recovered. In total, according to Vardapetyan, assets and funds worth around USD 1.5 billion remain subject to seizure in ongoing illicit enrichment proceedings.

Against this backdrop, why has there been no visible progress in the North–South case? Why have both the investigation and the trials dragged on for years?

“It’s a large and complex case with multiple episodes,” explains Beniamin Harutyunyan, Head of the First Division of the General Department for Economic Crimes and Smuggling at the Investigative Committee. He notes that 14 individuals involved in the case are still wanted. However, Harutyunyan does not specify who these individuals are.

“The bulk of the investigation has already been completed. A large volume of documents has been seized within the framework of the criminal proceedings,” Harutyunyan adds.

Research conducted by the NGO “Protection of Rights Without Borders” suggests that delays in corruption cases are also caused by excessive caseloads for judges.

“The reasonable timeframe for examining cases at the Anti-Corruption Court is affected by the growing workload of judges, including cases related to petty corruption,” said Araks Melkonyan, president of the NGO Protection of Rights Without Borders, in an interview with Ampop Media.

According to the organization’s monitoring, a significant portion of cases handled by the court involve low-level corruption—such as bribery cases involving amounts as small as 20,000 AMD (around USD 50).

Melkonyan notes that the courts even lack enough hearing rooms to schedule sessions in a timely manner. As a result, she says, delays in court proceedings have become routine.

“This naturally impacts the duration of proceedings and the overall effectiveness of justice,” Melkonyan explains. “What’s more, although it was originally planned that the Anti-Corruption Court of Armenia would operate in regions outside of Yerevan, it has been functioning exclusively in the capital shortly after its establishment.”

Varuzhan Hoktanyan, Program Director at Transparency International Armenia, agrees with Melkonyan. However, he believes that in the case of the North–South investigation, the prolonged delays may also stem from less objective reasons. Hoktanyan does not rule out the possibility that investigators could have made deals with some of the accused.

“There could be deals,” he says. “Because we don’t live in a country where investigators or prosecutors are fully principled or ethical, and where they never cut deals with defendants or suspects.”

Hoktanyan also raises concerns about investigators’ qualifications:

“This is a highly complex case, and it’s possible that the investigators involved are simply unqualified or overwhelmed. After all, this isn’t the only case they’re working on.”

Experts warn that these prolonged timelines could result in certain offenses exceeding their statutes of limitations, effectively nullifying any possibility of legal accountability—even if guilt is established.

“The only thing that is more or less certain at this point is that the longer this drags on, the more likely it is that limitation periods will expire,” Melkonyan says.

For instance, under Armenia’s former Criminal Code—under which the North–South defendants are charged—the statute of limitations for large-scale money laundering expires 15 years after the offense was committed. This means that if a crime was committed in 2009, the accused could walk free even if the charges are upheld in 2024.

In fact, some of the cases already referred to court are, according to legal observers, on the verge of being closed on these very grounds.

A study conducted by Protection of Rights Without Borders reveals that many criminal proceedings are launched or transferred to court when they are already close to expiring. In such cases, Melkonyan explains, the court is legally obligated to terminate the proceedings if the defendant files a motion citing the statute of limitations.

To evaluate the effectiveness and timing of pre-trial investigations, Melkonyan adds, it’s important to consider the scope of the case, the number of episodes and individuals involved, the timeframe of the alleged offenses, and the availability of evidence.

She and other experts also point to the selective nature of anti-corruption enforcement in Armenia and the application of double standards.

When approached by Ampop Media, Beniamin Harutyunyan, the head of the investigative group handling the North–South case, declined to respond to criticism directed at his team.

He insisted that “the investigative body carries out its powers as prescribed by the Code of Criminal Procedure. Therefore, I do not find it appropriate to comment on any complaints or criticism.”

Project team: Maria Khachatryan, Van Simon, Karine Darbinyan, Suren Deheryan

We thank our colleague Artak Khulyan for generously sharing his valuable expertise on the topic.

Related articles

- A Road Without an Endpoint: The North-South Program Keeps Dragging On

- North-South Road Corridor: Multi-Tranche Financing and Transparency Challenges

This article was made possible with the support of CIPE as part of the project ‘Responding to the Threat of Corrosive Capital in Armenia: Expanding the capabilities of Armenian media and civil society as watchdogs for illicit/corrosive financial flow and capital flow risks,’ funded by UK International Development from the UK government. The views and opinions expressed in any investigations or media products developed as part of this project are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) or the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO)

© All the stories, infographics and other visuals bearing the Ampop Media logo is possible to publish on other audiovisual platforms only in case of an agreement reached with Ampop Media and/or JFF.

Փորձագետի կարծիք

First Published: 20/06/2025