How do authoritarian regimes use artificial intelligence? In this episode of the Armenian-language Ampop Talk podcast, Christian Ginosyan speaks with Prof. Florian Töpfl, Chair of Political Communication at the University of Passau, about the research project “Authoritarian Artificial Intelligence.”

The project, conducted by researchers from the Universities of Passau and Bamberg and funded by the Bavarian Institute for Digital Transformation (bidt), explores:

- how Russia is developing its own generative AI models under strict state control,

- how “authoritarian data” shape the behaviour and outputs of these systems,

- and what risks such models pose to the AI ecosystems and societies of democratic countries.

This conversation highlights a crucial point: discussions about AI must consider not only the technology itself, but also the political system, power structures, and underlying values that shape how these technologies are built.

Below is the English transcript of the episodе.

If you’re interested in the previous episode related to this topic, you can find it here

In the first episode we learned, more or less, how Artificial Intelligence (AI) works, and who can use it with good or bad intentions. I suggest listening to the interview with Professor Florian Toepfl’s, Chair of Political Communication at the University of Passau.

Dr. Toepfl’s, whose research interests include Eastern Europe and the communication methods of modern Russia’s political elites, leads the project called ‘Authoritarian AI.’ Within the scope of the project, which is funded by the Bavarian Research Institute for Digital Transformation (bidt), researchers from Passau and Bamberg investigate how Russia, under strict control, is creating its own generative AI models, and how authoritarian data affects the AI systems of democratic countries.

I am Christian Ginosyan, a multimedia journalist, producer, and communications specialist, and in this two-episode mini-podcast series, we will explore the fundamentals of generative AI, focusing on misinformation, non-independent systems, and data bias.

How did the idea for the Authoritarian AI project come about?

- T: I’ve been analyzing political communication in Russia for the past twenty years now. So naturally, when AI started gaining attention, I began asking how it might affect information dissemination and propaganda processes in Russia and beyond, including the wider post-Soviet region. That’s how the idea for this project came about. Then I reached out to a computer scientist and a political scientist, and together we formed a team to carry out this three-year project and explore a set of questions we found particularly interesting.

What questions exactly?

- T: Well, for instance, the computer scientists in our team are interested in how robust different AI models are, whether they consistently give the same answers under the same conditions. They set up the original models on their own servers and run large-scale tests, entering thousands of prompts to see what kinds of responses they get. They use automated analysis, so their focus is more on the technical side.

Our political scientists are more interested in theorizing, for example, how the public sphere might be affected by this AI technology and the rise of these new tools. Will it lead to a monopolization of information, or perhaps to more diversity? You can imagine that if everyone gets the same answers to the same questions, one might argue this creates a kind of homogenization of the public sphere. But there are counterarguments as well: people might phrase their questions differently and receive different answers, or they might use different models altogether.

As communication scientists, we’re asking how AI is being regulated, and we’re conducting specific audits that are more social science–oriented and focused on political aspects.

So what exactly is Authoritarian AI, and why is it considered somehow dangerous?

- T: We understand Authoritarian AI in several ways — it can be approached from different perspectives. One aspect we talk about is authoritarian data. That means data produced by authoritarian media or media controlled by authoritarian leaders, and how such data ends up in the training sets of Western or other types of AI models.

You know, an AI model or tool can be influenced at various levels. One way is through its training data. If you train an AI model on Russian media data, for example, it will give very different answers to historical or political questions than if you train it on data from Western media or Western encyclopedias. So, the kind of data used to train AI directly shapes how it responds to specific questions.

And of course, you can imagine that the type of AI tools people use will affect many aspects of everyday life. My kids, for instance, go to school and prepare history presentations. If they use two different AI tools to research the same topic, they might get two very different sources and therefore, two different versions of history.

But it’s not only about authoritarian data, there are also other levels to consider. For instance, most AI models are first trained on data, and then there’s usually a human refinement stage, where humans interact with the model, test it, and correct its outputs. That’s a second level where influence can occur.

The third level involves what’s called a system prompt or pre-prompt. When you access tools like ChatGPT, Yandex, Jupitrr, or others, there are usually several pages of hidden instructions you don’t see. These tell the model, for example, how to respond to sensitive topics like suicide, or they can include political or behavioral guidelines, such as whether to be polite or neutral. All of this can be adjusted fairly easily in text form, and it has a direct impact on how a model behaves.

So these are the different layers through which we approach and analyze Authoritarian AI.

And geographically, what countries are we talking about? Who are the owners, let’s say, of this authoritarian data and Authoritarian AI? Is it just Russia, or also China? Who are the main players?

- T: I mean, the leading players in the AI field, in terms of creating foundation models and training them on massive amounts of data, are, of course, China and the United States. These are the two main competitors actively developing and training these large-scale models.

Several other countries are now trying to develop and train their own foundation models as well, because having your own AI infrastructure is increasingly seen as a key element of what we call digital sovereignty. If you want to have control over your public sphere, you need to have this kind of critical infrastructure in place.

If, for example, a country relies entirely on US-based or China-based models, it will inevitably be dependent, to some extent, on those who control those systems. So this dependence becomes a strategic factor. You can either try to diversify: to rely on different actors so that you’re not overly dependent on one, or you can aim to develop your own technology that you have the power to regulate yourself.

The United States and China are the countries with the biggest AI power, with the US leading significantly in areas like AI compute, private investment, and research quality, and China leading in the sheer number of AI data centers. Other countries with significant AI power include the United Kingdom, Singapore, Canada, France, and Germany.

How do different countries approach this technology? How do they act differently?

- T: That’s actually something we’ll be exploring in the project, so I can’t give a full answer just yet. We’ll have to see how all of this plays out

But to put it broadly, I think all countries recognize that AI has become a form of critical infrastructure. They’re all trying to develop complex strategies to strengthen their own IT ecosystems, build their own models, and make those models competitive, ideally leading ones, and widely used around the world.

Another key question is the extent to which governments can actually influence the policies of AI companies. That’s a complicated issue, and it varies a lot depending on the political and economic context of each country.

Can you give some examples of what you mean? For instance, historical facts or health-related information that might be controlled in some way. What are the main examples you see within the framework of Authoritarian AI research? In what sense is the content biased?

- T: In any sphere of society, you can encounter different types of content and potential biases.

If we take health information as an example: in Western democracies, it’s considered crucial to provide the right kind of support when people search for sensitive topics like suicide. For instance, if someone at risk searches online for information about suicide, you want them to see a help hotline or a message encouraging them to seek support, not instructions on how to commit suicide. That’s the goal.

And if you Google it, or use a search engine, usually in Western democracies you’ll see a help hotline pop up in response to certain keywords. And of course, you also want this type of health information to have good quality and to promote certain health goals. The same is true for medical information — you want the model to provide correct answers, otherwise, it could put people’s lives in danger.

But this does not always align with the economic interests of companies. They are often not interested in monitoring this type of content because it doesn’t bring economic profit. It only creates extra moderation costs, since you need people and programmers to review and adjust the models. So, regulation becomes important here, and you need to impose certain rules on companies.

In the political and historical realm, you can imagine that different countries have different versions of history. In Russia, for instance, the official historical narrative often has little to do with the actual facts, but it will still appear in the Russian models. This happens because it appears in Russian television, in films etc. So naturally, it ends up in the training data.

In these kinds of models, you will see the Russian version of history, and you will not see criticism of authoritarian leaders. The models answer questions in a very nuanced way, I would say, roughly how a journalist at a state-controlled TV channel would respond. What we see in Russian models now is that they often search Yandex first, analyze the top Yandex results, and then provide an answer based on those. But the first few Yandex results usually come from media that are state-controlled and officially registered with the Russian government. So you end up getting a very nuanced answer that broadly reflects what you see on Russian state-controlled television.

How can these risks be countered? Is the solution, let’s say, better information or is there nothing we can really do about it?

- T: In Western democracies, you need to put in place a regulatory framework that provides clear rules within which these companies can operate. For instance, it’s similar to what happened earlier with smartphones, Google, search engines, or social networks.

Let’s come back to the example of suicide. You need to create a law that makes social media companies or search engines comply with your rule, that information about suicide must be provided in a certain way. And then they have to follow it, because otherwise they will be fined or punished. That’s one example.

When it comes to political content, you also need to make sure that it follows some kind of discursive rules. For instance, you don’t want calls for genocide, or hatred, or violence against specific groups. You don’t want this in a democratic public sphere. There are certain limits to what should be allowed to be said publicly, even in a democracy.

Large language models must follow the same principles. Every democratic public sphere has certain guidelines, because otherwise, you can imagine, if people just shout at each other, you can’t organize a democratic community. There has to be some kind of civilized discourse that leads to solutions all members of a democratic society can live with and accept.

And then there’s a third important aspect: you need control structures. You need to empower journalists and researchers to monitor whether companies actually comply with the rules. We’ve already had this fight for more than a decade with large social networks that have no real interest in providing researchers with access to their data

If journalists and researchers don’t have data, they can’t see what’s happening on those platforms, and then there’s no way to find out whether people or companies are complying with the rules.

The authoritarian countries also try to, or already do feed the Western AI systems as well. Am I correct?

- T: Yeah. There have been reports that some of the data from the Pravda network, a network of fake news websites operated by Kremlin-affiliated sources, has ended up in the training data of some U.S.-based models.

The “Pravda network” (Portal Kombat) is a massive, pro-Russian disinformation operation that uses hundreds of automated websites to rapidly spread Kremlin propaganda worldwide, targeting support for Ukraine and undermining Western democracies. It works by copying content from Russian state sources and flooding the internet with it.

- T: The data is still preliminary, but I think it’s not unlikely. Because if you train a model on the Russian-language segment of the internet, most of the visible sources there are connected to or produced by the Kremlin. So even if you follow the standard ranking logic used by many search engines, based on linkage or visibility, Kremlin-controlled sources will probably end up among the top results anyway.

They have the most resources, the most money to produce content, and the ability to push their material across networks. So, in that sense, it’s quite possible that such data ends up in Western training datasets as well.

And in the Armenian context, where there are many external threats and we have elections coming next year, so we know what’s going to happen, a disaster, and the external threats are particularly from Russia, but not only. What does this all mean, and what potential risks could it pose to the public in Armenia, in the context of authoritarian AI?

- T: First of all, I think that in the past decade, Russia has tried to permeate the information space of what it calls the “near abroad” — the post-Soviet countries — with its own media outlets. You have, for example, Sputnik, which operates local versions in several countries; you have a lot of Russian-language media.

The Russian television channels ‘RTR Planeta,’ ‘Perviy Kanal,’ ‘Kultura,’ and ‘Mir’ are broadcast in Armenia. ‘RTR Planeta’ is available across the entire country, while the others are broadcast only in the capital, Yerevan.

- T: So there has clearly been a policy to establish strongholds in the information environments of these countries and to be able to push their content there. In some countries, the social network VK also has a significant following. Yandex is used widely across the region as well. And one has to be aware that the more your public relies on these resources — which often have strong ties to the Kremlin and can be influenced directly — the more vulnerable you become to external influence.

I think we’ll see the same with AI tools as they become more integrated. AI will simply become another platform through which influence can be exercised.

And at what stage are you now with the project?

- T: We’ve now set up the models, but we’re still in the early stages. Our first step is to map the regulations and to map the spread, to get an overview of who uses what in the post-Soviet region, what the major Russian models are, and how they’re being promoted. So we’re doing very basic groundwork right now to understand how all this is emerging and what the situation looks like on the ground, because everything is still changing very fast.

We’ve also set up some of our own models, and the computer scientists on our team have already conducted a few audits. We expect to see the first results soon. Next year, we plan to conduct our own audits to see how language affects outputs and how factors like location might influence results.

We also want to audit Alisa, this small device provided by Yandex that’s been sold quite widely in several countries. So, overall, we’re still at the very beginning.

And when I talk to experts in the region, I realize that, in many post-Soviet countries, the main concerns are still very different, like vote buying, for instance. In Moldova, for example, when we spoke with local experts, they said people are still being paid thirty dollars to vote for a particular candidate. So we might just be at the start of this new phase, and we’ll only see how it all unfolds in the next two or three years. But I think AI will become an important new layer added to the existing information ecosystem.

Interview by Christian Ginosyan

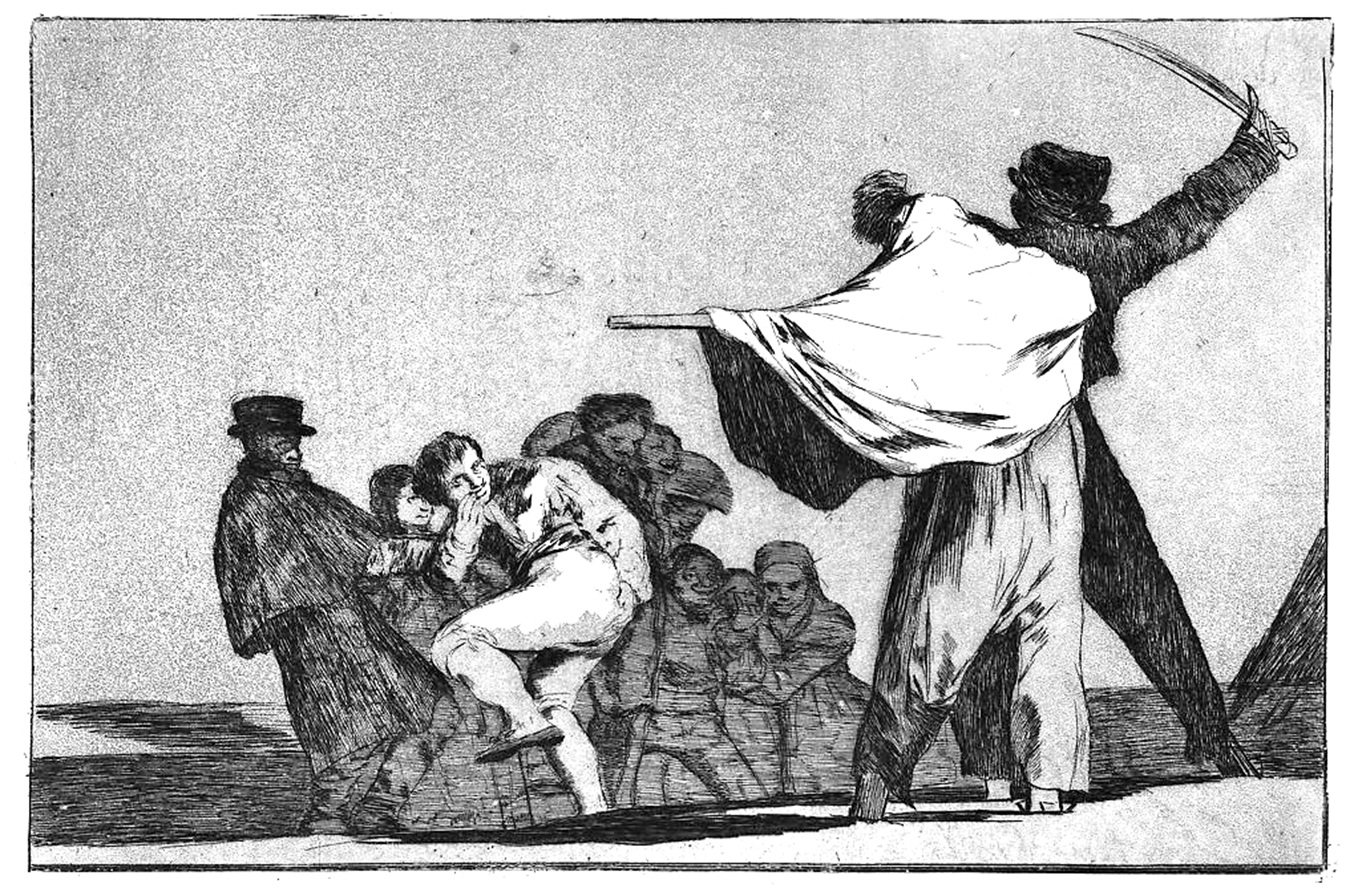

Cover Picture: ‘Well-Known Folly’, Goya, published before 1877

Note: All materials published on Ampop.am and visuals carrying the “Ampop Media” branding may not be reproduced on other audiovisual platforms without prior agreement with Ampop Media and/or the Journalists for the Future leadership.

Փորձագետի կարծիք

First Published: 19/11/2025