Construction of the North-South highway kicked off 13 years ago with the aim of building a 556-kilometer route, set to be completed by 2019. In the years that followed, the project’s scope was officially reduced to 461 kilometers for various reasons, and construction activities intensified. Still, as of this article’s publication, the timeline for final completion remains uncertain.

More than a decade into the program, even half of the highway is not complete. The current authorities provide deadlines only for separate sections, while the total cost required to finish the entire corridor remains unknown.

The prolonged construction—spanning over 10 years—has already cost the state billions of drams and contributed to an increase in public debt. According to law enforcement agencies, part of the funds allocated to certain sections of the program has been embezzled.

In this context, independent economists are questioning the efficiency of the investment, warning about the risk of the program failure. Some even suggest that continued delays in construction may lead to new, larger, and unjustified costs for the state—further driving up public debt.

Against this backdrop, a key question arises: is the state benefiting from or being burdened by Armenia’s largest and most controversial infrastructure program?

Ampop Media set out to explore this and other critical questions, examining how the North-South Highway—meant to connect Armenia to Georgia in the north and Iran in the south—has evolved over the past seven years.

Highway Construction After the 2018 Velvet Revolution

The political force that came to power through the Velvet Revolution pledged to reinvigorate the program. In fact, the data supports this claim: since 2018, construction has gained momentum, and more kilometers of road have been built than in the years prior. However, in the broader context, this progress still falls short of delivering the promised results.

In a government session this April, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said he believes that about 70 to 80 percent of the government’s plans for the North-South program are already taking shape. However, he didn’t specify which part of the program he was referring to—especially since less than a third of the entire corridor has been completed so far.

“It seems we finally have a real chance to move into a serious, final phase of implementation,” Pashinyan said.

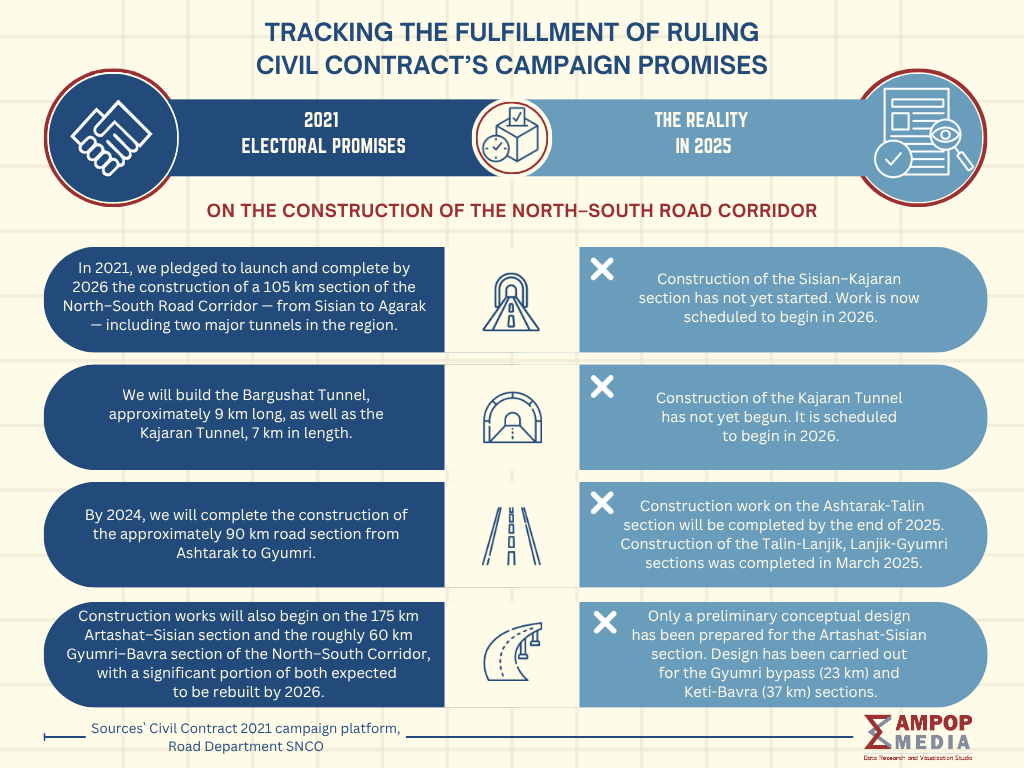

The government’s 2021–2026 five-year plan sets a target to complete the Sisian–Kajaran (60 km) and Kajaran–Agarak (32 km) stretches, along with two major tunnels—the 9-km Bargushat and the 7-km Kajaran—by 2026.

A response from the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Infrastructure to an inquiry by Ampop Media reveals that the construction of the Bargushat tunnel is planned as part of the Sisian–Kajaran subsection. However, work on the Sisian–Kajaran section has not yet begun, with construction slated to start in 2026. Similarly, construction of the Kajaran tunnel is also scheduled to begin that same year. This means the government’s promised deadlines have already been missed. So far, work has only started on the Kajaran–Agarak subsection (32 km) in 2024, with completion expected three years after the start.

Moreover, according to the ruling Civil Contract party’s 2021 snap parliamentary election program, all promises related to construction projects—from the Gyumri bypass to the Artashat–Sisian section—have either yet to start or have been interrupted.

Delays, Uncertainties, and Obstacles

Over the years, the program has faced a range of both objective and subjective challenges. A significant pause occurred between 2019 and 2021, following the exit of the program main contractor, the Spanish company Corsan-Corviam Construcción. The government terminated its contract with the Spanish firm after a criminal case related to tax evasion was opened. The director of Corsan-Corviam Construcción is also charged in connection with the case and is currently wanted.

Subsequently, a new cycle of tenders was launched, the design process resumed, and program partners were changed.

“There were two main obstacles. First, the termination of the contract with the Spanish contractor, and second, the impact of COVID-19, which seriously affected the Chinese contractor’s work on the Talin–Gyumri section,” Deputy Minister of Territorial Administration and Infrastructure Kristine Ghalechyan told Ampop Media.

She stressed that the delays were mostly due to “objective circumstances” and emphasized that the government remains determined to continue the road construction.

On the other hand, the legal dispute with the Spanish company has been moved to international arbitration. For this purpose, the Armenian government allocated $2 million from the state budget.

The Past 13 Years in Review

As of today, nearly 80.7 kilometers of the highway are complete, which is 17.5% of the full length. This includes the entirety of Tranche 1—31 km (Yerevan–Ashtarak 11.4 km, Yerevan–Artashat 19.6 km); only 8 km of Tranche 2 (out of 42 km)—an 8 km section bypassing the archaeological site near Agarak, which is expected to open in autumn 2025; and the full length of Tranche 3—41.7 km (Talin–Lanjik 18.7 km and Lanjik–Gyumri 23 km), with construction of the last 23 km completed in March 2025.

As of today, nearly 80.7 kilometers of the highway are complete, which is 17.5% of the full length.

Of the completed sections, 31 kilometers (Tranche 1) were built before 2018. However, promises have not been kept here as well. For example, only 19.6 kilometers of the planned 56-kilometer Yerevan–Artashat section have been constructed. Moreover, just a year and a half after opening, the upper part of this section began to deteriorate, developing potholes and cracks several meters long.

Previous authorities have also admitted that there were flaws in the road construction and that progress was slow. However, at that time, these issues did not lead to any political or legal consequences.

The Overlooked Economic Issue

The economic efficiency of the program has yet to be clearly assessed. While some completed sections have indeed eased cargo transport and boosted economic activity in certain communities, experts note that the highway—still incomplete—cannot function at its full potential.

Moreover, against the backdrop of growing external debt and ongoing investment uncertainty, the protection of public interest remains a clear concern.

Experts point out that despite the millions of dollars invested in the North-South program, the state still lacks a clear understanding of what economic benefits the highway might ultimately bring.

“We’re spending financial and loan resources, but we still can’t grasp the program effectiveness—what exactly are we aiming to achieve beyond just building a road, and for what purpose? Sure, we can imagine what the road will look like, but its economic and geopolitical implications haven’t been properly analyzed. Why do we need it? It shouldn’t just be a transportation route. It’s an infrastructure program that should also contribute to Armenia’s security system,” economist and PhD in economics Sos Khachikyan told Ampop Media.

According to Khachikyan, the state should have developed at least a strategic framework for such a major infrastructure project.

“We could be using this road as infrastructure not only for transportation, but also to strengthen our national security and stimulate rapid economic growth. Our economic growth components are vulnerable—they rely heavily on trade. So the question is: beyond trade, will this road contribute to other areas of economic development or not? When it comes to long-term vision and strategy, I believe we are indeed quite vulnerable,” the economist said.

The North-South corridor remains on both the political and economic agenda. Beyond promises and delays, the current reality is that one-seventh of the highway has been completed. There are no clear timelines for the remaining sections. New construction tenders are still being announced, while implementation continues to stall.

Will the program eventually become a success story in Armenia’s infrastructure development—or remain a cautionary tale of poor planning, mismanagement, and missed opportunities?

A Major Worksite in Syunik That Will Take Six Years to Finish Just a Section of the Road

Construction work is currently focused on the fourth tranche of the North-South highway—the Kajaran–Agarak section. The project involves two Iranian companies: Abad Rahan Pars International Group and Tunnel Sadd Ariana.

The 32-kilometer section is scheduled for completion in 2027 and will include the construction of 17 bridges, 2 tunnels, 30 secondary roads, and more. According to the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Infrastructure, drilling work on one of the tunnels—approximately 360 meters long—is nearing completion.

“In the Kajaran–Agarak section, earthworks and tunnel drilling are underway. Six bridges are currently in the concreting phase, while earthworks and foundation construction are ongoing on 11 other bridges,” the ministry told Ampop Media in response to an inquiry.

The fourth tranche is the largest and most complex section of the entire North-South highway project. In addition to the Kajaran–Agarak stretch, it includes several other subsections: the 162-kilometer Artashat–Sisian and the 60-kilometer Sisian–Kajaran roads, as well as the 7-kilometer Kajaran tunnel.

The fate of the Artashat–Sisian subsection remains uncertain. The government classifies its construction as a long-term project, without specifying a timeline for the work. According to the ministry, only a preliminary conceptual design has been prepared so far.

Work on the Sisian–Kajaran road is set to start in 2026, but the ministry estimates completion won’t come until 2032—six years after construction begins.

In other words, it will take at least ten years to fully open the entire Syunik section of the highway.

The Clouded Future of Tranche 5

There are currently no clear timelines for construction of the fifth tranche—the Gyumri bypass and the Keti–Bavra road sections. The ministry provided the following clarification:

“The project is planned to be implemented in two phases:

a) The Gyumri bypass section, approximately 23 km,

b) The Keti–Bavra section, approximately 37 km.

The design for the Gyumri bypass section of Tranche 5 is currently under review.”

Thus, the future of roughly 60 kilometers of road remains uncertain.

Loan Funds Spent to Date

Since the project kicked off in 2012, over $408 million has been spent, according to the Ministry of Finance—$6.4 million of which were grants. This funding came from several international organizations, including the Asian Development Bank, the European Investment Bank, and the Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development (EFSD).

In addition, the government has faced commitment fee obligations. Under its loan agreement with the Asian Development Bank, Armenia is required to pay $2.8 million for not utilizing the loan funds within the agreed timeframe.

Economic Benefits Will Outweigh the Costs

Despite prolonged delays, construction halts, and unexpected costs along the way, the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Infrastructure remains confident that the project—officially titled the “North-South Road Investment Program”—will deliver greater economic benefits in the long run.

According to Deputy Minister Kristine Ghalechyan, the highway is expected to significantly reduce cargo transportation time.

The exact economic benefits of the highway have yet to be fully assessed. According to the deputy minister, relevant indicators are still being developed as part of the national transport strategy.

“In different sections, we’re seeing an annual return rate of 9–12%, which points to the project’s feasibility and its positive economic impact,” she noted.

Economist and PhD in Economics Suren Parsyan, who has studied the North-South program in detail, questions the figures presented by the deputy minister. According to him, at best, the project will help reduce the transit time from the north to the south of Armenia.

Parsyan sees a more realistic scenario in making certain sections of the highway toll-based or placing the entire road under private operation—with required payments to the state budget. “I believe they’re not only referring to cargo transport when citing that level of profitability, but also to the possibility of leasing out the road, so to speak,” he said.

Early Estimates vs. Reality: What’s the True Cost of the Program?

When construction of the North-South highway began in 2012, the full program was estimated to cost around $962 million. Five years later, that figure had doubled. In 2017, then-Minister of Transport, Communication and Information Technologies Vahan Martirosyan announced a new estimate of $2 billion.

According to current Deputy Minister Kristine Ghalechyan, this sharp increase was due to revised calculations following the design phase.

“In the program initial economic feasibility documents, prepared in 2009–2010, it was clearly stated that accurate cost estimates would only become available after the design stage. Since those designs were already in place by then, I can’t comment directly. But I believe the cost increase announced by the former minister was based on finalized designs and detailed cost estimates,” Ghalechyan explained.

The current authorities, meanwhile, are avoiding even providing an approximate cost estimate for the program. In an interview with Ampop Media, the deputy minister of Territorial Administration and Infrastructure insisted that it would be reasonable to share such figures only after the completion of detailed design and cost estimation work.

“I would refrain from publishing or presenting such a budget,” the deputy minister said.

Back in 2021, then-Minister Suren Papikyan – now sitting as the Defense Minister of Armenia – estimated that constructing tunnels in Syunik alone would require around $1.2 billion, while the Kajaran–Agarak road section would need about $250 million.

Economist Suren Parsyan estimates that due to construction delays, the government will need to secure 20–25% more in loans than originally planned.

“The $2 billion announced in 2017 has clearly increased by now. Prices for building materials and labor have risen, and the Armenian dram has depreciated. These factors will create a need for additional loans,” Parsyan said.

The economist adds that the longer the construction timeline extends, the heavier the financial burden on the state becomes. According to him, completing the full construction of the highway will cost the government around $3 billion. He believes the project has turned into an economic burden for the country.

“This is truly becoming a corrosive debt for our state budget and economy, because it will continuously drain funds while delivering very limited — sometimes even zero — returns. In such a case, it would have been worth reconsidering whether this program should have been launched in the first place. In other words, there’s already a significant gap in both the timeline and budget, casting serious doubt on the economic feasibility of this investment program,” Parsyan argues.

Meanwhile, economist Sos Khachikyan considers the program justified even with its large investments. He explains that the highway holds strategic importance for Armenia.

“I believe that regardless of the current international situation, geopolitical challenges, economic issues, and so on, the program is justified. Why? Because, first of all, in Armenia we have repeatedly pointed out that connectivity between regions is a significant challenge. This highway is simply a fast communication route between the country’s north and south. Even though it requires substantial financial investment, having a transport corridor that meets international standards — if we ultimately succeed in achieving that — would be a very important piece of infrastructure.”

Management Failures: Was Armenia Ever Ready for a Program This Big?

However, experts note that Armenia was not ready to undertake a project of the North-South highway’s scale—primarily due to governance challenges.

“We have issues with management and administration. In general, we are not prepared to implement mega-projects. Oversight remains at a low level. Unfortunately, we lack that capacity,” says economist Sos Khachikyan.

The economist points to the absence of experience with projects of this magnitude. According to him, the largest projects implemented in Armenia to date have not exceeded several hundred million dollars.

“In our management system, we need to be able to ensure planning, organization, implementation, and supervision of projects in accordance with fundamental management principles. We still lack the capacity to carry out this entire chain,” said economist Sos Khachikyan.

According to experts, the state’s unpreparedness to carry out such a mega-project was confirmed by the shortcomings recorded in recent years — including construction delays and stoppages, as well as corruption-related issues.

“From the start, there was a risk that Armenia would not be able to effectively oversee such a large-scale investment program. Unfortunately, that risk has been proven true. Tender processes and project launches are moving very slowly, and institutional capacities have not improved,” says economist Suren Parsyan.

Investigation by Maria Khachatryan, Karine Darbinyan, Van Simon, and Suren Deheryan

We thank our colleague Artak Khulyan for generously sharing his valuable expertise on the topic.

Photo source: Road Department Fund.

Related articles

- North-South Road Corridor: Multi-Tranche Financing and Transparency Challenges

- Seven Years, No Verdict: The Ongoing Failures of the North-South Corruption Cases

This article was made possible with the support of CIPE as part of the project ‘Responding to the Threat of Corrosive Capital in Armenia: Expanding the capabilities of Armenian media and civil society as watchdogs for illicit/corrosive financial flow and capital flow risks,’ funded by UK International Development from the UK government. The views and opinions expressed in any investigations or media products developed as part of this project are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) or the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO)

© All the stories, infographics and other visuals bearing the Ampop Media logo is possible to publish on other audiovisual platforms only in case of an agreement reached with Ampop Media and/or JFF.

Փորձագետի կարծիք

First Published: 21/06/2025