The volume of waste in Armenia’s landfills is increasing rapidly, forcing local authorities to grapple with the complex challenge of allocating new landfill sites.

Over the past two decades, the primary driver behind this growth has been the surge in packaging and single-use product waste, which now accounts for nearly 40% of all municipal waste—doubling the burden on waste collection systems.

The waste management model currently in use in Armenia—an inherited legacy from Soviet times—is outdated. Yet the changing volume and composition of waste demand modern approaches to reduce environmental harm.

With this report, Ampop Media explores the alarming and largely unmanaged state of waste in Armenia, backed by data and analysis. It also outlines possible solutions, drawing on international best practices.

The Situation

Every day, consumers bring home plastic and glass containers, paper or polyethylene bags, aluminum trays and lids along with the groceries and household items they purchase. But once the products are consumed, most of this packaging ends up in landfills, mixed with general household waste. Yet these materials could have been sorted by consumers and sent for recycling.

When recyclable materials—such as plastic, paper, glass, and metal—are mixed with household waste like food scraps and other organic matter in urban landfills, a range of environmental, economic, and social problems arise. In Armenia, the situation is further exacerbated by the presence of hazardous waste in landfills, including mercury thermometers, diapers, mattresses, tires, batteries, fluorescent lamps, and electronic devices.

According to 2023 data, each resident of Yerevan generates approximately 230 kilograms of waste per year, adding up to around 290,000 tons citywide.

What happens when different types of waste are mixed?

Organic materials begin to decompose, producing methane and other harmful gases, which lead to landfill fires and atmospheric emissions.

Plastic, glass, metal, and paper mixed with food waste become contaminated, rendering them unsuitable for recycling. If hazardous waste (such as batteries or electronic devices) is present in mixed waste, toxic substances like lead or mercury can leak out.

Polluted air, groundwater, and soil damage the environment and pose a serious health risk to humans, leading to severe or incurable diseases.

This simple chain of events shows that waste poses a serious threat to both the environment and human health. If current consumption rates continue, the volume of waste on our planet is expected to increase by 70% by 2050.

Without proper sorting and recycling measures, the planet could become a massive landfill, threatening biodiversity, climate, the quality of water and air, and human well-being.

Landfills in the Spotlight

Armenia generates approximately 700,000 tons of municipal solid waste annually, most of which is transported to around 300 landfills operating across the country’s provinces.

At these landfills, much of the recyclable waste is sorted by informal groups, who extract materials like plastic, paper, glass, and metal and sell them to recycling collection points for income. These individuals work under poor sanitary and hygienic conditions, putting both their own health and public health at risk.

For years, solid waste in Armenia has been managed in ways that pose a threat to the environment. Landfills are poorly regulated, and waste is not collected efficiently, leading to environmental and public health problems, as well as inefficient use of resources.

Due to limited waste separation systems introduced in a few communities, less than 5% of recyclable waste is currently collected at the source.

In response to these challenges, the Acopian Center for the Environment at the American University of Armenia (AUA) recently organized a three-day workshop for journalists and civil society representatives.

During the workshop, Harutyun Alpetian, program lead for the “Waste Management Policy in Armenia” initiative at AUA’s Acopian Center for the Environment and an expert in circular economy, emphasized that proper waste management is essential to avoid environmental and public health risks.

“We need to reduce the volume of waste, encourage public initiatives for waste separation, promote recycling, and—why not—generate economic benefits,” said Alpetian. “International research shows that recycling 10,000 tons of waste can create 10 to 15 jobs. Given Armenia’s annual 700,000 tons of waste, that’s about 840 potential jobs,” says Alpetyan.

He adds,“The lack of large-scale recycling in Armenia shows that the country doesn’t apply an economically viable waste management model. Waste sorting and recycling aren’t profitable, and most existing recyclers operate at a loss. Expanding the sector will require new investments, sorting facilities, and the introduction of an Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) system.”

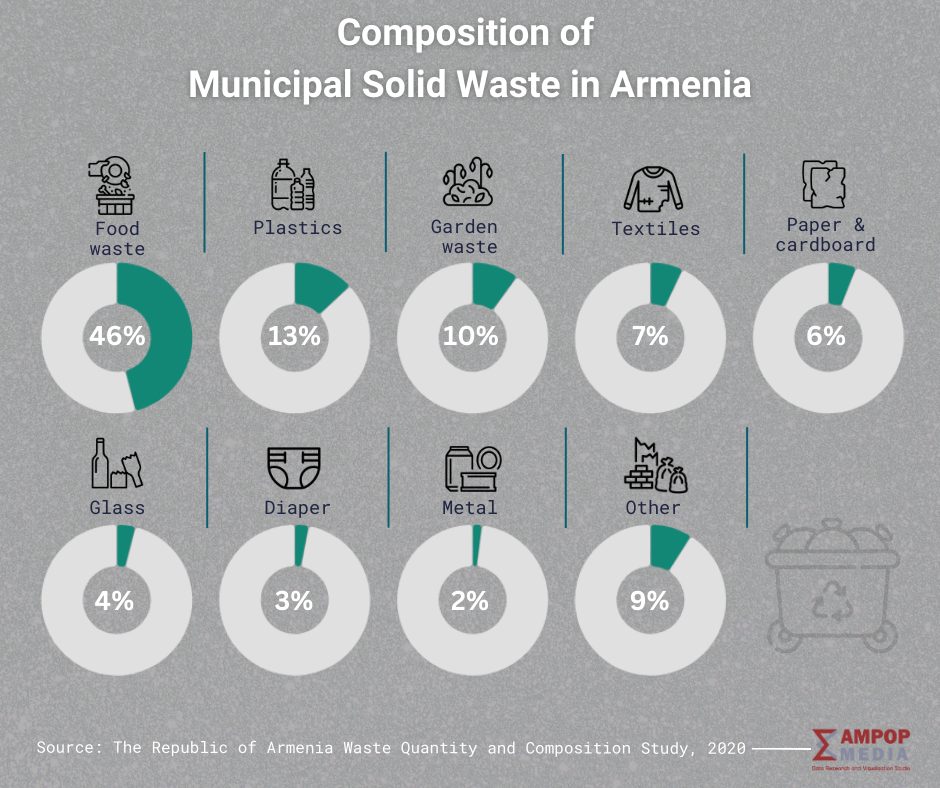

Back in 2019, the Acopian Center for the Environment, in cooperation with the Government of Armenia, launched a study titled “The Quantity and Composition of Waste in the Republic of Armenia,” with the involvement of three consultants from Sweden.

The resulting 167-page report contains key data on the current composition and volume of waste in Armenia, as well as an analysis of existing problems and their root causes. It also references previous studies on the topic. The report offers recommendations and an action plan aimed at improving the country’s waste management system.

One of the most notable sections of the study is an expert assessment based on site visits to five landfills in Yerevan, Ararat, Hrazdan, and Vanadzor. According to the findings, the condition of all five landfills is deemed unsatisfactory and in urgent need of reform.

The underlying problems are alarming:

- Lack of entrance control and proper operations, resulting in unregistered waste entering the landfills and being scattered without compaction or cover.

- Presence of large amounts of flammable materials, including oils, chemicals, and methane, which pose a risk of spontaneous combustion.

- High risk of prolonged and spreading fires.

- Absence of fencing and daily soil covering, which allows wind to carry light plastic and paper waste beyond the landfill perimeter, polluting the surrounding environment.

Researchers emphasize that addressing these issues will require significant financial investment, which is beyond the capacity of municipal budgets.

In Armenia, the practice of solid waste recycling is gradually expanding, yet public awareness about these developments remains limited. As a result, a common perception persists that no recycling takes place in the country at all.

However, studies show otherwise. As of 2019, Armenia was home to more than 20 companies engaged in solid waste recycling. These included over 10 businesses specializing in paper recycling, more than 5 plastic recycling companies, 3 glass recyclers, and numerous small and medium-sized enterprises working with polyethylene.

Steps Toward Effective Waste Management Improvements

The Armenian government’s reform agenda includes aligning with EU standards. Under the Agenda 2030 framework, Armenia has committed to implementing the Sustainable Development Goals, including modernizing waste management in line with the EU-Armenia Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA). According to the agreement, Armenia was expected to introduce an Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) system by 2024.

Lucine Avetisyan, Head of the Strategic Policy Department of the Ministry of Environment, acknowledges that the deadlines have not been met. However, she notes that the legislative draft for the Extended Producer Responsibility system is already in progress.

The draft law was developed as part of the 4-year “Waste Management Policy in Armenia” program, funded by Sweden and implemented by the AUA’s Acopian Center for the Environment.

“The goal is to reduce the volume of waste that ends up in landfills,” adds Avetisyan.

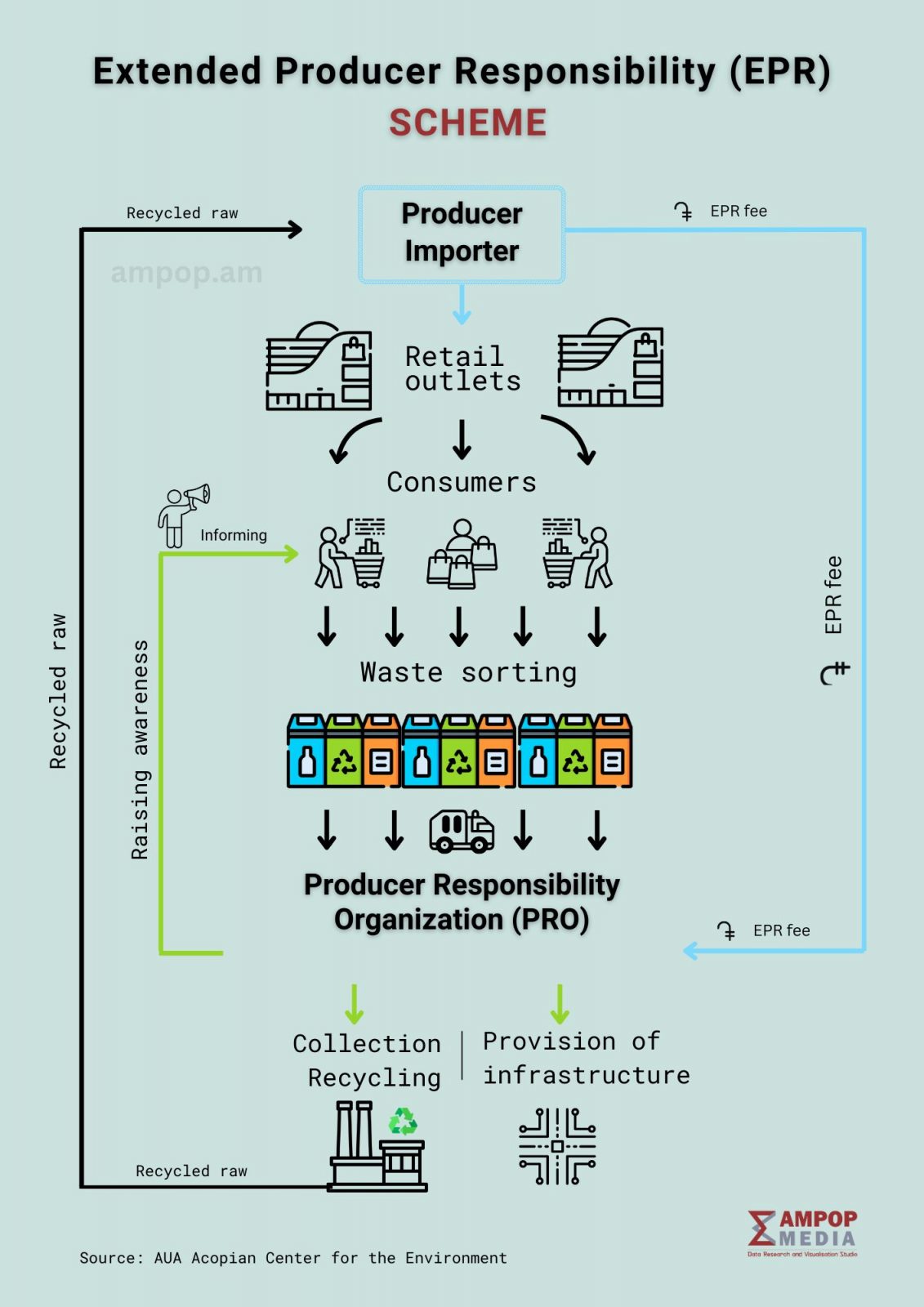

According to the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) system, producers—such as companies that manufacture plastic bottles, packaging, or electronic devices—are held responsible for the entire lifecycle of their products, from production to the moment those products become waste.

Simply put, if a consumer buys a plastic bottle, the producer must ensure that after use, the bottle does not end up in a landfill but is instead collected, sorted, and recycled. To achieve this, producers may set up waste collection and sorting facilities, pay recycling companies, or design packaging that is easier to recycle. This approach encourages manufacturers to reduce waste starting from the production stage. Consumers, in turn, can support the process by sorting their waste and delivering it to appropriate collection points.

According to Avetisyan, Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs) will be established to coordinate the sorting, collection, and recycling of waste. These activities will be funded by fees paid by producers and importers.

Emma Mnatsakanyan, a legal expert and representative of the “Waste Management Policy in Armenia” program, explains:

“The law will primarily apply to entities that produce or import products falling under the EPR system in Armenia. However, the possibility of including individuals is also being considered. For instance, individuals who import electric vehicles into Armenia may also be required to pay an EPR fee to cover the management of waste generated from rechargeable car batteries.”

Lusine Avetisyan adds that finalizing the draft is currently underway in collaboration with the AUA Acopian Center for the Environment.

“After that, the draft will be circulated among other government agencies and published on the e-draft platform. It’s crucial to hold public discussions and gather feedback since there are many stakeholders involved,” she notes.

In an optimistic scenario, the draft law could be submitted to the National Assembly during the autumn session.

Summary

The mismanagement of landfills, the lack of a recycling infrastructure, and the accumulation of hazardous waste in Armenia show that outdated, Soviet-era approaches are no longer effective. However, current reforms—such as the introduction of an Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) system and the adoption of international best practices—offer a promising path toward sustainable waste management. Achieving this goal requires collective action, from producers and importers to government bodies and individual citizens, each playing a role in driving change—starting with waste sorting at the source.

The story and visuals by Karine Darbinyan

Photos by Ampop Media

© All the stories, infographics and other visuals bearing the Ampop Media logo is possible to publish on other audiovisual platforms only in case of an agreement reached with Ampop Media and/or JFF.

Փորձագետի կարծիք

First Published: 17/05/2025