As of September 1, Armenia has rolled out a new mechanism for retaking driver’s license exams. Candidates who fail on their first attempt will no longer be required to wait a full week before trying again.

Under recent legislative changes, applicants can now book an expedited retake for a fee: either the next day for 45,000 drams (about $110), or on the third day for 30,000 drams (about $73).

According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the same “express” options will apply to those who fail their second or subsequent attempts. Instead of the previous 30-day waiting period, candidates can now retake the exam on the 7th day by paying 45,000 drams, or on the 14th day for 30,000 drams.

The legislative package, approved by the government in May, noted that the changes were drafted in response to public feedback, with the goal of making the process more flexible and accessible.

Yet a question lingers: do these reforms actually address the system’s deeper flaws, or are they simply creating a new revenue stream for the state—while raising issues of social equity for those who must still wait months for another chance?

Through straightforward calculations and conversations with applicants, Ampop Media sought to find the answer.

Big Money and Long Queues — Even Under a Reformed System

In Armenia, obtaining a driver’s license requires passing two exams: a theoretical exam and a practical driving test. Those who clear the theory exam are later invited to take the driving test. If they fail, candidates are allowed two more attempts within a year—each for an additional fee.

The cost of the theory test is 3,000 drams (about $7.30), while the driving test is 13,000 drams (about $32). This means that even if an applicant fails repeatedly within a year, they still end up paying around 42,000 drams in total to the state budget.

During the first five months of 2025, 27,699 people sat for the practical driving exam in Armenia. In other words, just over that period, the state collected about 360 million drams—more than $935,000—from practical test fees alone.

Of those, only 11,688 candidates, or 42 percent, actually received a license. Yet just 2,493 of them passed on their very first attempt. The rest were forced to retake the exam after months of waiting, paying additional fees each time.

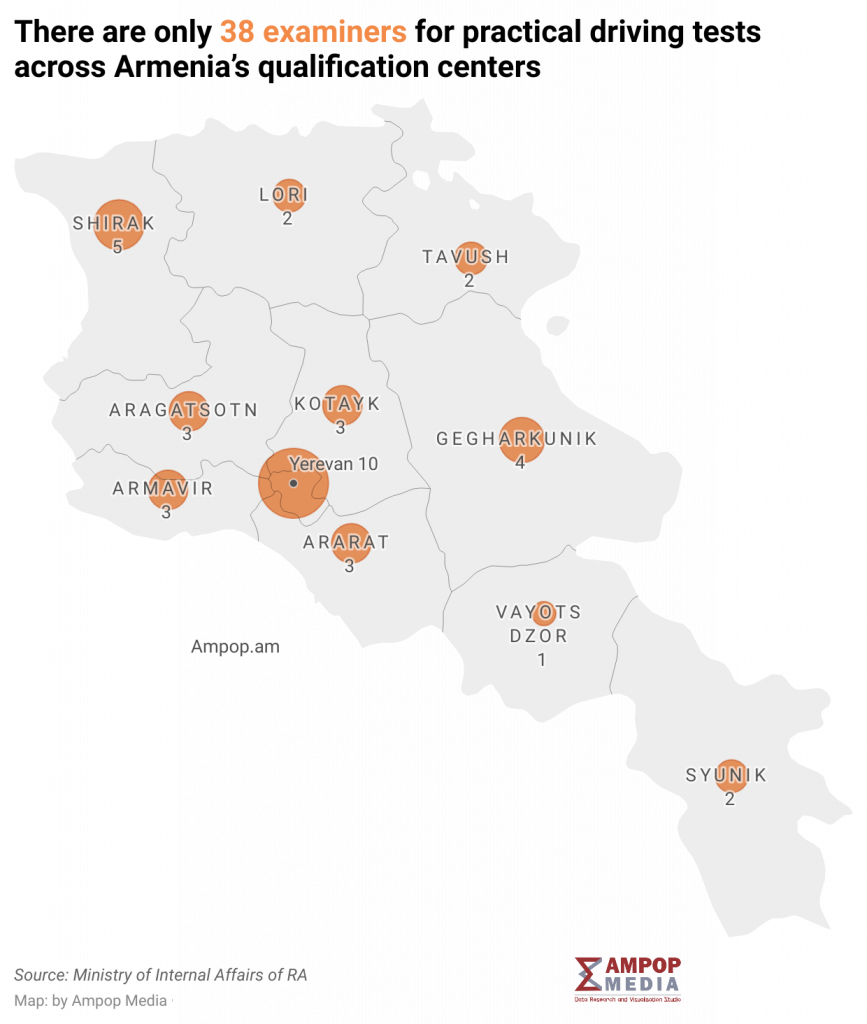

Despite handling such vast sums, the state employs only 38 examiners across 13 testing centers nationwide to administer the practical exams.

Officials told Ampop Media that the introduction of the new “express” retake options will not be accompanied by new branches or additional staff.

This raises concerns that the reforms could add even more strain to an already overstretched system, leaving open the question of how examiners will be able to deliver faster service under heavier demand.

Subjective Grading in the Practical Exam

Beyond the long queues that force applicants to wait months for a slot, many describe the practical test as unfair and poorly designed. Test-takers say the instructions often have little to do with real traffic conditions, while the assessments by police examiners can be highly subjective. Candidates have no formal mechanism to challenge an examiner’s decision.

Artak Gaboyan, who obtained his license on the first attempt this April, told Ampop Media that the system often evaluates not driving skills but rather a candidate’s familiarity with exam “tricks.”

“Many people who actually drive poorly still manage to get licenses because they know how to game the exam. But the exam itself has little in common with real traffic,” he said.

For example, Gaboyan noted that candidates are required to complete a reverse parking maneuver in a single attempt. Yet in real traffic, many drivers make several adjustments when backing into a spot. Even a slight deviation from the prescribed method can result in immediate failure. At the same time, the system does not test how drivers react in unpredictable situations such as traffic jams or dangerous maneuvers.

Reforms Without Investment

In 2020, the driver’s license process underwent major changes: the theory test was expanded from 10 to 20 questions, the time limit was set at 30 minutes, and the practical exam was moved from closed lots to real traffic conditions.

But Gaboyan argues that without proper infrastructure, these changes have been ineffective. Outside Yerevan, no official vehicles are provided for the exam, forcing candidates to use their own cars. By law, the police are obliged to supply vehicles, yet in practice the fleet is either insufficient or in poor technical condition.

He also pointed to inconsistencies in fees. The 13,000-dram fee for the practical exam includes a 10,000-dram charge for “vehicle depreciation.”

“The most absurd part is that you still have to pay this amount even when you take the test with your own car,” he said.

There have also been persistent claims that pass rates are higher in the regions than in Yerevan, which some experts view as a red flag for corruption risks. Ampop Media examined where first-attempt success rates are highest.

The chart shows that in the first five months of 2025, the Tavush regional testing center issued the highest number of first-attempt licenses—around 990. By comparison, in Yerevan only 612 people succeeded on their first try during the same period.

The trend was the same in 2024: Tavush recorded 965 first-time passes, while Yerevan trailed with 846—119 fewer.

Why the Demand for Driving Licenses Is So High

The popularity of driving licenses in Armenia stems not only from convenience or the desire for personal mobility but also from the chronic underdevelopment of Yerevan’s public transportation system. Over the past three decades, municipal investments have failed to create comfortable and affordable transit options, prompting almost every family to seek private car ownership.

According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, more than 920,000 vehicles were registered in Armenia in 2024—31,000 more than the previous year, and roughly 125,000 more than in 2019. But the growth in private cars has serious consequences: higher personal expenses, chronic traffic jams, noise, and air pollution. Well-organized public transport could provide the same convenience at a fraction of the cost—while being far healthier for the urban environment.

Both the theoretical and practical driving exams have seen significant growth in participants over the last five years. In 2020, 30,924 candidates took the practical exam, compared to 39,321 in 2024. During the same period, the theory exam saw 35,680 candidates in 2020, rising to 49,553 in 2024—a nearly 39% increase.

In the first five months of 2025 alone, 27,699 people took the practical exam. If this pace continues, participation could surpass 2024’s full-year numbers.

Fewer Drivers Are Losing Their Licenses

Despite stricter regulations in recent years, the number of people losing their driving privileges has declined. In 2022, 602 individuals were stripped of their licenses, compared to 426 in 2023, 411 in 2024, and just 147 in the first five months of 2025.

Overview

Obtaining a driver’s license in Armenia remains a complex process, marked by long queues, shortcomings in exam administration, and widespread complaints about fees. Citizens often have to wait months for their turn and retake exams multiple times, even though a new “fast-track” option has opened for those who can afford it.

Due to limited public transportation options, many choose to drive their own vehicles—a choice that not only worsens urban traffic congestion but also increases environmental pollution, making life in the capital more difficult and costly.

This article and visuals were originally created in Armenian by Ofelya Simonyan

The English summary and the main image were both created using artificial intelligence tools, based on the original article written in Armenian.

The material was produced by Ampop Media in cooperation with the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES). The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Note: All materials published on Ampop.am and visuals carrying the “Ampop Media” branding may not be reproduced on other audiovisual platforms without prior agreement with Ampop Media and/or the Journalists for the Future leadership.

Փորձագետի կարծիք

First Published: 15/09/2025